And something we should congratulate ourselves for as well.

This was mentioned only briefly in part of a short article in The Economist a few weeks ago about how the few last countries are banning tetraethyl lead. I'm glad to see a much longer treatment here. Apparently we've done ourselves a lot more good by getting lead out of paint and motor fuel than we thought. And a reason to look twice more at new regulations which might have as great a benefit.

___________________________________

http://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2 ... connection

Crime Is at its Lowest Level in 50 Years. A Simple Molecule May Be the Reason Why.

—By Kevin Drum

| Thu Jan. 3, 2013 3:06 AM PST

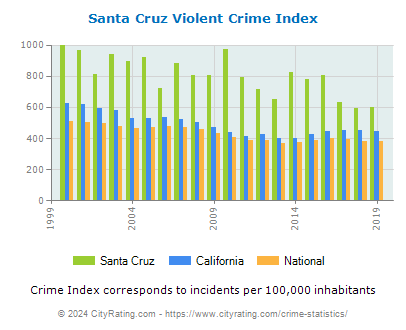

I've written several posts recently about the idea that America's great crime epidemic, which started in the 60s and peaked in the early 90s, was caused in large part by lead emissions from automobiles. Long story short, we all bought lots of cars after World War II and filled them up with leaded gasoline. This lead was spewed out of tailpipes and ingested by small children, and when those children grew up they were more prone to committing violent crimes than normal children. Then, starting in the mid-70s, we all began switching to unleaded gasoline. Our kids were no longer made artificially violent by lead poisoning, and when they grew up in the mid-90s they committed fewer violent crimes. This trend continued for two decades, and it's one of the reasons that violent crime rates have dropped by half over the past 20 years and by more than that in our biggest cities. It's one of the great underreported stories of our time: big cities today are as safe as they were 50 years ago.

That's the short version of the story. The long version of the story is on the cover of the current issue of Mother Jones, and today it's available online for the first time. Click here to read it. The chart on the right illustrates the basic data that inspired the lead hypothesis: it shows lead emissions starting in 1935 overlaid with the violent crime rate 23 years later. The two curves match almost perfectly. ... ".

3

3This link has the full article:

http://www.motherjones.com/environment/ ... k-gasoline

"...

"Gasoline lead may explain as much as 90 percent of the rise and fall of violent crime over the past half century."

intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the same upside-down U pattern. The only thing different was the time period: Crime rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the '80s, and then began dropping steadily starting in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dove in further, digging up detailed data on lead emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned out to be even better: In a 2000 paper (PDF) he concluded that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and '50s really were more likely to become violent criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetraethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking and pinging in high-performance engines. As auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers in powerful new cars increasingly asked service station attendants to "fill 'er up with ethyl," they were unwittingly creating a crime wave two decades later. ... "

"... The answer, it turned out, involved "several months of cold calling" to find lead emissions data at the state level. During the '70s and '80s, the introduction of the catalytic converter, combined with increasingly stringent Environmental Protection Agency rules, steadily reduced the amount of leaded gasoline used in America, but Reyes discovered that this reduction wasn't uniform. In fact, use of leaded gasoline varied widely among states, and this gave Reyes the opening she needed. If childhood lead exposure really did produce criminal behavior in adults, you'd expect that in states where consumption of leaded gasoline declined slowly, crime would decline slowly too. Conversely, in states where it declined quickly, crime would decline quickly. And that's exactly what she found.

Meanwhile, Nevin had kept busy as well, and in 2007 he published a new paper looking at crime trends around the world (PDF). This way, he could make sure the close match he'd found between the lead curve and the crime curve wasn't just a coincidence. Sure, maybe the real culprit in the United States was something else happening at the exact same time, but what are the odds of that same something happening at several different times in several different countries?

Nevin collected lead data and crime data for Australia and found a close match. Ditto for Canada. And Great Britain and Finland and France and Italy and New Zealand and West Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other astonishingly well. When I spoke to Nevin about this, I asked him if he had ever found a country that didn't fit the theory. "No," he replied. "Not one." ... "

"...Other recent studies link even minuscule blood lead levels with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Even at concentrations well below those usually considered safe—levels still common today—lead increases the odds of kids developing ADHD.

In other words, as Reyes summarized the evidence in her paper, even moderately high levels of lead exposure are associated with aggressivity, impulsivity, ADHD, and lower IQ. And right there, you've practically defined the profile of a violent young offender. ... "

___________________________________

yrs,

rubato