We all know that a lawyer cannot lie on behalf of his client. Two Three questions:

1). If the lawyer believes it to be true and he later finds that his statement was false, is that a defense?

2). Is there a difference between these two statements: a) My client was out of town on the night in question; and b) My client says he was out of town on the night in question?

3). Is an attorney under oath in the same way that a witness is? I think that s/he does not take an oath at the same time as a witness but is it understood in some way? If an attorney does knowingly lie can s/he be sanctioned in some way or prosecuted for perjury? Do they take some sort of blanket 'lifetime' oath when they qualify?

Legal question

-

ex-khobar Andy

- Posts: 5837

- Joined: Sat Dec 19, 2015 4:16 am

- Location: Louisville KY as of July 2018

- Sue U

- Posts: 9131

- Joined: Thu Apr 15, 2010 4:59 pm

- Location: Eastern Megalopolis, North America (Midtown)

Re: Legal question

Do you have a specific set of facts and circumstances in mind? Like all legal questions, the answer is always "it depends," but generally lawyers are prohibited by the Rules of Professional Conduct from making any false statements of material fact; when and what type of corrective measures need to be taken may vary according to the circumstances. Some more specific answers may be found in the ABA's Model Rules of Professional Conduct, which is the template for the RPCs adopted by individual states. So:ex-khobar Andy wrote: ↑Sun Jan 08, 2023 5:54 pmWe all know that a lawyer cannot lie on behalf of his client. Two Three questions:

1). If the lawyer believes it to be true and he later finds that his statement was false, is that a defense?

2). Is there a difference between these two statements: a) My client was out of town on the night in question; and b) My client says he was out of town on the night in question?

3). Is an attorney under oath in the same way that a witness is? I think that s/he does not take an oath at the same time as a witness but is it understood in some way? If an attorney does knowingly lie can s/he be sanctioned in some way or prosecuted for perjury? Do they take some sort of blanket 'lifetime' oath when they qualify?

1). If the lawyer believes it to be true and he later finds that his statement was false, is that a defense?

First, a defense to what? A conflict of interest, an ethics complaint, a perjury charge, a crime or fraud, something else? In court? Under oath? Made to a third party? Made to a client/prospective client? Made to an opposing party or lawyer? Made to a court or other tribunal? Did or should the lawyer undertake a reasonable investigation of the facts?

Generally, RPC 4.1 provides that "In the course of representing a client a lawyer shall not knowingly: (a) make a false statement of material fact or law to a third person; or (b) fail to disclose a material fact to a third person when disclosure is necessary to avoid assisting a criminal or fraudulent act by a client, unless disclosure is prohibited by Rule 1.6 [attorney-client confidentiality]."

2). Is there a difference between these two statements: a) My client was out of town on the night in question; and b) My client says he was out of town on the night in question?

Yes, obviously, in the sense of describing who is making the factual representation. But the circumstances under which such statements might have been made can have a significant impact. For example, RPC 3.4 prohibits an attorney from asserting s/he has personal knowledge of the facts in issue during a trial. But if you're talking more informally to opposing counsel or a prosecutor on behalf of the client, the meaning may be the same, i.e., "upon information and belief, the facts will tend to show that my client was out of town."

3). Is an attorney under oath in the same way that a witness is? I think that s/he does not take an oath at the same time as a witness but is it understood in some way? If an attorney does knowingly lie can s/he be sanctioned in some way or prosecuted for perjury? Do they take some sort of blanket 'lifetime' oath when they qualify?

An attorney takes an oath on admission to the bar and is otherwise bound by the RPCs, but does not take any oath at trial (or in trial-adjacent proceedings like depositions) unless actually called as a witness (in which case it's generally a bad idea to be acting as the advocate in the first place, but there are rules about that, too). And attorneys are subject to prosecution and various court-imposed penalties for perjury, suborning perjury, and other general fuckery in court proceedings, as well as disciplinary proceedings before whatever entity regulates the bar in the state (reprimand, suspension, disbarment, etc.).

Specifically when dealing with a court (or other adjudicative body), RPC 3.3 provides: "(a) A lawyer shall not knowingly: (1) make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer; (2) fail to disclose to the tribunal legal authority in the controlling jurisdiction known to the lawyer to be directly adverse to the position of the client and not disclosed by opposing counsel; or (3) offer evidence that the lawyer knows to be false. If a lawyer, the lawyer’s client, or a witness called by the lawyer, has offered material evidence and the lawyer comes to know of its falsity, the lawyer shall take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal. A lawyer may refuse to offer evidence, other than the testimony of a defendant in a criminal matter, that the lawyer reasonably believes is false."

Further, "(b) A lawyer who represents a client in an adjudicative proceeding and who knows that a person intends to engage, is engaging or has engaged in criminal or fraudulent conduct related to the proceeding shall take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal, and "(d) In an ex parte proceeding, a lawyer shall inform the tribunal of all material facts known to the lawyer that will enable the tribunal to make an informed decision, whether or not the facts are adverse."

Hope this helps.

GAH!

Re: Legal question

So a lawyer may put a criminal defendant on the stand while "reasonably believing" that testimony to be false? How is that not suborning perjury? Or does a lawyer require absolute certainty of its falsity in order to suborn perjury?A lawyer may refuse to offer evidence, other than the testimony of a defendant in a criminal matter, that the lawyer reasonably believes is false.

"Hang on while I log in to the James Webb telescope to search the known universe for who the fuck asked you." -- James Fell

- Sue U

- Posts: 9131

- Joined: Thu Apr 15, 2010 4:59 pm

- Location: Eastern Megalopolis, North America (Midtown)

Re: Legal question

I don't do criminal law, so I don't know all the ins and outs, but the comments on the rule say:Scooter wrote: ↑Tue Jan 10, 2023 5:38 pmSo a lawyer may put a criminal defendant on the stand while "reasonably believing" that testimony to be false? How is that not suborning perjury? Or does a lawyer require absolute certainty of its falsity in order to suborn perjury?A lawyer may refuse to offer evidence, other than the testimony of a defendant in a criminal matter, that the lawyer reasonably believes is false.

[7] The duties stated in paragraphs (a) and (b) apply to all lawyers, including defense counsel in criminal cases. In some jurisdictions, however, courts have required counsel to present the accused as a witness or to give a narrative statement if the accused so desires, even if counsel knows that the testimony or statement will be false. The obligation of the advocate under the Rules of Professional Conduct is subordinate to such requirements. See also Comment [9].

[8] The prohibition against offering false evidence only applies if the lawyer knows that the evidence is false. A lawyer’s reasonable belief that evidence is false does not preclude its presentation to the trier of fact. A lawyer’s knowledge that evidence is false, however, can be inferred from the circumstances. See Rule 1.0(f). Thus, although a lawyer should resolve doubts about the veracity of testimony or other evidence in favor of the client, the lawyer cannot ignore an obvious falsehood.

[9] Although paragraph (a)(3) only prohibits a lawyer from offering evidence the lawyer knows to be false, it permits the lawyer to refuse to offer testimony or other proof that the lawyer reasonably believes is false. Offering such proof may reflect adversely on the lawyer's ability to discriminate in the quality of evidence and thus impair the lawyer's effectiveness as an advocate. Because of the special protections historically provided criminal defendants, however, this Rule does not permit a lawyer to refuse to offer the testimony of such a client where the lawyer reasonably believes but does not know that the testimony will be false. Unless the lawyer knows the testimony will be false, the lawyer must honor the client’s decision to testify. See also Comment [7].

GAH!

- Sue U

- Posts: 9131

- Joined: Thu Apr 15, 2010 4:59 pm

- Location: Eastern Megalopolis, North America (Midtown)

Re: Legal question

Related, and hot off the presses from the NJ Disciplinary Review Board a couple of weeks ago. Lawyer represented client pleading guilty to "first-offense" DUI in one town's court and later that same day pleaded the same client guilty to "first offense" DUI in another town. Apparently, that's Not. Cool.

You may have noticed a reference in the story above to the attorney's "lack of appropriate remorse or contrition," and to be fair it's not always clear when you have to disclose what in these kinds of situations. Below is an article that pretty well summarizes the legal background to this most recent disciplinary decision, and you can see how the attorney might have convinced himself that he was not violating the RPCs. However, this is also a hazard of solo practice -- not having another attorney around to give you a reality check on issues that may push the edges of "zealous representation."NEWS

'Misrepresentation Cannot Serve as a Permissible Litigation Tactic,' Says Disciplinary Review Board

A Cherry Hill attorney with no prior disciplinary record received a censure after representing that his client was a first-time DWI offender in two different municipal court proceedings on the same day, according to a decision issued by the Disciplinary Review Board.

On the morning of Dec. 18, 2017, attorney David S. Bradley and his client, Edward Coyle, appeared in the Berlin municipal court, where Coyle entered a guilty plea for a DWI as a first offender, according to the decision.

Later that afternoon, Coyle and Bradley appeared in the Stratford municipal court in the matter of a second DWI incident. Again, Coyle entered a guilty plea to DWI and the prosecutor recommended he be sentenced as a first offender, according to the decision.

“Coyle’s driver’s abstract had not yet been updated to reflect his Berlin DWI conviction from that same morning and, thus, neither the Stratford municipal court nor the prosecutor were aware of Coyle’s prior conviction,” stated the Disciplinary Review Board decision. “Coyle provided the court with a factual basis for his plea, and the court, upon examining Coyle’s driver’s abstract, asked respondent whether Coyle was a first-time offender.”

“’I looked at the driver’s abstract,’” Bradley stated in court, according to the DRB decision. “‘It was just run today, Judge. There are no priors.’”

According to the DRB decision, the Stratford municipal court sentenced Coyle to the mandatory minimum penalties for a first-time DWI offender. And, the decision stated, Bradley knew that Coyle’s driver’s abstract had not been updated to reflect the guilty plea entered that morning in Berlin. This matter was previously before the board on Oct. 21, 2021, on a recommendation by the District IV Ethics Committee of an admonition for Bradley. The DRB “determined to treat the admonition as a recommendation for greater discipline, pursuant to R. 1:20-15(f)(4), and to bring the matter on for oral argument.”

The formal ethics complaint, according to the DRB decision, charged Bradley with RPC 1.4(c)—failure to explain a matter to the extent reasonably necessary to permit the client to make informed decisions regarding the representation; RPC 3.3(a)(5)—failure to disclose to a tribunal a material fact knowing that the omission is reasonably certain to mislead the tribunal; RPC 8.4(c)—conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation; and RPC 8.4(d)—conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice.

“At the ethics hearing, in his answer to the formal ethics complaint, and at oral argument before us, respondent claimed that he was unaware, at the time of Coyle’s court appearances, that his tactic was unethical,” stated the DRB decision. “Specifically, respondent believed that he had no responsibility to provide the Stratford municipal court or prosecutor with information detrimental to Coyle, even when it would impact a mandatory sentence, based on the principles in State v. Kane.”

“Incredibly, respondent also rationalized that he would have been found ‘ineffective’ for disclosing Coyle’s prior conviction from that same morning,” stated the decision.

The DRB decision stated that Bradley failed to appreciate his duty of candor to the court. But despite that lack of understanding, the DRB stated that Bradley ”admitted that he had ‘deceived’ the municipal court and prosecutor into believing that Coyle was a first offender, in violation of RPC 3.3(a)(5), RPC 8.4(c), and RPC 8.4(d).”

As to the charge of violating RPC 1.4(c) by failing to discuss with Coyle the risks inherent in being sentenced twice as a first offender, Bradley denied he committed a violation. The DEC agreed with Bradley and found that he did not, by clear and convincing evidence, violate RPC 1.4(c).

“Ultimately, respondent’s refusal to comply with his duty of candor led the Stratford court to improperly sentence Coyle as a first-time DWI offender, instead of the increased penalties he should have faced as a subsequent offender,” stated the decision. “Respondent’s dishonesty in response to a direct question from the court further constituted conduct prejudicial to the administration of the justice system, in violation of RPC 3.3(a)(5); RPC 8.4(c); and RPC 8.4(d).”

The DRB found that there is insufficient evidence to prove, by clear and convincing evidence, that Bradley violated RPC 1.4(c).

“As the DEC correctly found, and as respondent testified, respondent did not appear to have a premeditated strategy to mislead the Stratford municipal court into sentencing Coyle as a first-time offender,” stated the decision.

The range of disciplinary measures generally imposed for the violations committed by Bradley range from reprimand to a long-term suspension, according to the decision.

“In aggravation, based on respondent’s unreasonable justifications for his misconduct and his ongoing lack of appropriate remorse or contrition, we find that he not only has failed to appreciate the seriousness of his deception, but also has failed to understand that misrepresentation cannot serve as a permissible litigation tactic, even when carried out in the name of zealous advocacy,” stated the decision.

“Although respondent’s misconduct placed him on the precipice of a suspension, in light of his otherwise unblemished career, we determine to impose a censure and note that, going forward, respondent must adhere to the duty of candor required of all attorneys in order ‘to comply with the high standards that our profession demands,’” stated the decision.

Seven members of the DRB voted for censure, while Chair Maurice Gallipoli voted for a three-month suspension. The New Jersey Supreme Court issued an order imposing a censure on Bradley for violation of RPC 3.3(a)(5); RPC 8.4(c); and RPC 8.4(d).

NJ Lawyers have no duty to disclose a client’s indictable offense

February 26, 2015 By Schneider Freiberger, P.C.

The New Jersey Law Journal reported the following case, which has a bearing on how all lawyers conduct themselves in regards to defending municipal court and superior court defendants in New Jersey:

A lawyer whose client pleaded guilty in municipal court to the traffic offense of driving with a suspended license was not obligated to inform the judge and prosecutor that the client was subject to indictment and harsher penalties because her license had been suspended for drunken driving, a New Jersey appeals court has held.

The court, however, faulted the lawyer, Steven Kaplan, for having his client, Davi Kane, later withdraw the guilty plea without explaining to her that she would lose her protection against double jeopardy and be exposed to prosecution for a fourth-degree crime carrying a minimum half-year in jail, which is what eventually occurred.

In an unpublished Feb. 17 opinion in State v. Kane, a three-judge panel found ineffective assistance of counsel by Kaplan, a Northfield, New Jersey, solo, and upheld a lower court decision that reinstated the original plea.

DWI defense lawyer Jeffrey Gold of Cherry Hill, New Jersey, who was not involved in the case, said Kane answered a question that has been “a big practice issue for the bar: Is it your job as defense attorney to bring up to the prosecutor that this could be an indictable charge?”

Gold said he sees the issue now as whether that should be the judge’s responsibility, adding that he does not think it should.

Gold said he plans to ask the state bar association and the Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers of New Jersey to request that Kane be published as a decision by a three-judge panel “on an important issue of law that should guide the behavior of lawyers.”

In Kane, Appellate Division Judges Jack Sabatino, Marie Simonelli and Michael Guadagno rejected the prosecution’s position that Kaplan engaged in fraud and violated ethics rules on the initial plea by not alerting the municipal judge and prosecutor that his client’s conduct could be prosecuted as a fourth-degree crime.

The panel said there was insufficient evidence of that. The panel also noted that Kane’s driving abstract was available to the judge and prosecutor and should have revealed that Kane was on the revoked list because of multiple DWI convictions, making her eligible to be charged with violating N.J.S.A. 2C:40-26(b).

The panel acknowledged that the statute, which became law in 2009 and carries a minimum 180-day jail term, was “relatively new” at the time of the initial March 2012 plea, and, thus, “it is conceivable that the judge and prosecutor may not have been well-attuned to its potential application in DWI cases.”

But the panel nevertheless rejected the contention that ethics rules required defense counsel “to spotlight the statute’s potential application adverse to his client’s interests.”

The panel did not view the situation as akin to In re Seelig, where the New Jersey Supreme Court held in 2004 that a lawyer violated his duty of candor to the court by having a client plead guilty to reckless driving in a hit-and-run accident, without disclosing that the accident killed two people.

In that case, according to the opinion, the prosecutor was plea-bargaining outside the courtroom, and, when the judge asked the attorney, Jack Seelig, if the accident caused personal injury or property damage, Seelig answered, “personal injury.”

Despite finding an ethics breach, the Supreme Court opted not to penalize Seelig, saying it would be unfair because he acted under a good-faith but mistaken belief “that he had a superseding obligation to his client,” and there was a lack of clear judicial guidance on the issue.

But the justices made it clear that in the future, lawyers would have to reveal pending indictable offenses in order to prevent the court from being misled by their silence.

The Kane court called Seelig “markedly distinguishable” because in Seelig “a defense attorney affirmatively misled a municipal judge about the facts in a vehicular case, i.e., whether the victims had died.”

In contrast, the panel noted, the municipal prosecutor in Kane, Donald Charles, conceded it was his responsibility to be aware that the 2C offense might apply and not to accept the plea to a lesser charge with double-jeopardy implications.

Kane was arrested in Ocean City, New Jersey, on Jan. 25, 2012, for driving while under a 10-year license suspension for multiple DWI convictions. She was stopped because she was talking on a cellphone while driving.

About two months later, represented by Kaplan, she appeared before Judge Richard Russell in Ocean City municipal court and pleaded guilty to driving while suspended under Section 39:3-40 of the motor vehicle law, a nonindictable offense carrying at least 10 days in jail, but no more than 90, according to the panel’s opinion. Russell sentenced her to 30 days, which could be served intermittently, under an alternate incarceration program.

Five days later, Kane returned to court with Egg Harbor City, New Jersey, solo Shaun Byrne and withdrew the plea without being questioned by the judge, according to the opinion. Municipal court staff contacted Kaplan based on “concerns that came to the attention of the municipal judge that the plea may have been, as the judge termed it, ‘illegal,’” because of the potential indictable offense.

Following the plea withdrawal, Kaplan was indicted on the 2C charge and pleaded guilty in the Law Division, with the state recommending the minimum 180-day sentence, according to the opinion.

Kane hired a new lawyer and sought to withdraw her plea, but Judge Patricia Wild, of Cape May County, New Jersey, refused and later denied reconsideration, saying Kane had potentially viable double-jeopardy and ineffective assistance arguments that should be pursued by way of post-conviction relief. Wild imposed a 30-day sentence.

On Kane’s first appeal, decided in 2013, Sabatino and Judge Carmen Messano remanded so Kane could file a PCR petition and for a hearing on why her lawyers had her withdraw the first plea and admit to the more serious crime. The judges also instructed that if the PCR case failed, the sentence should be increased to 180 days.

The Feb. 17 appeals court opinion described what happened on remand.

Kaplan testified that he was aware of Kane’s driving record and that she was subject to indictment, but he denied that he considered the double-jeopardy implications.

He further testified that when he learned the court had relisted Kane’s case, he thought the judge had decided to reject the plea because of the possible indictment.

Kaplan claimed he had a scheduling conflict, that it was Kane who arranged for Byrne to accompany her and that he never discussed Kane’s case with Byrne.

Byrne, on the other hand, said he talked with Kaplan, who told him to withdraw the guilty plea, according to the opinion.

Byrne further testified that he advised Kane against it and she instructed him to do what Kaplan wanted.

Kane testified that Kaplan had called her a few days after the plea, saying there had been a mistake and that she had to return to court to take the plea back, because, if she didn’t, a warrant would be issued for her arrest, according to the opinion.

Kane recalled Byrne telling her he was uncomfortable with the withdrawal but said they did not discuss the possible consequences, according to the opinion. It was only after pleading guilty to the 2C crime that she realized she could go to jail for six months, Kane testified.

In July 2014, Wild found ineffective assistance by Kaplan, but not Byrne, though neither advised Kane of the 180-day sentence.

Wild said she believed Byrne’s account that he spoke with Kaplan before the plea withdrawal. The judge criticized Kaplan for abandoning Kane by not getting a postponement when he could not be there or arranging for competent counsel to appear on his behalf.

Wild vacated the second guilty plea, dismissed the indictment based on double jeopardy and reinstated the initial plea and sentence.

In affirming, the appeals court said Kaplan’s “improvident decision to have defendant withdraw her guilty plea to the municipal charges, especially since her guilt of driving on the suspended list was clear, surely was prejudicial to her in losing her double-jeopardy protection.”

The panel also expressed its view that there was “nothing illegal” about pleading guilty to the motor vehicle violation as a lesser-included offense to the fourth-degree crime.

Kane’s lawyer on appeal, Assistant Deputy Public Defender James Smith Jr., said he was pleased his client would not be spending 180 days in jail.

Byrne, Charles and Assistant Cape May County Prosecutor Gretchen Pickering declined to comment. Kaplan did not return calls seeking comment.

GAH!

-

ex-khobar Andy

- Posts: 5837

- Joined: Sat Dec 19, 2015 4:16 am

- Location: Louisville KY as of July 2018

Re: Legal question

Thank you Sue for the very detailed explanation. I probably had in mind Trump and the classified documents at Mar-a-Lago and then George Santos and his resumé 'embellishments'. But it's more complicated than that.

I spent a career in environmental science. As a scientist you are obligated to tell the truth regardless of where it leads. So I could (and sometimes did) say to a household name agricultural chemical company who were a multimillion dollar customer 'Sorry ABC Chemicals - your product which you hoped would be the next Round-Up and earn you billions kills rainbow trout babies at the 10 part per billion level. You're gonna have to think again.' I might put it more tactfully but that's the exec summary. Whenever the lawyers got involved -- theirs and/or ours -the truth became muddied. Being a scientist it's easier to believe in absolute truth.

I spent a career in environmental science. As a scientist you are obligated to tell the truth regardless of where it leads. So I could (and sometimes did) say to a household name agricultural chemical company who were a multimillion dollar customer 'Sorry ABC Chemicals - your product which you hoped would be the next Round-Up and earn you billions kills rainbow trout babies at the 10 part per billion level. You're gonna have to think again.' I might put it more tactfully but that's the exec summary. Whenever the lawyers got involved -- theirs and/or ours -the truth became muddied. Being a scientist it's easier to believe in absolute truth.

- Bicycle Bill

- Posts: 9820

- Joined: Thu Dec 03, 2015 1:10 pm

- Location: Living in a suburb of Berkeley on the Prairie along with my Yellow Rose of Texas

Re: Legal question

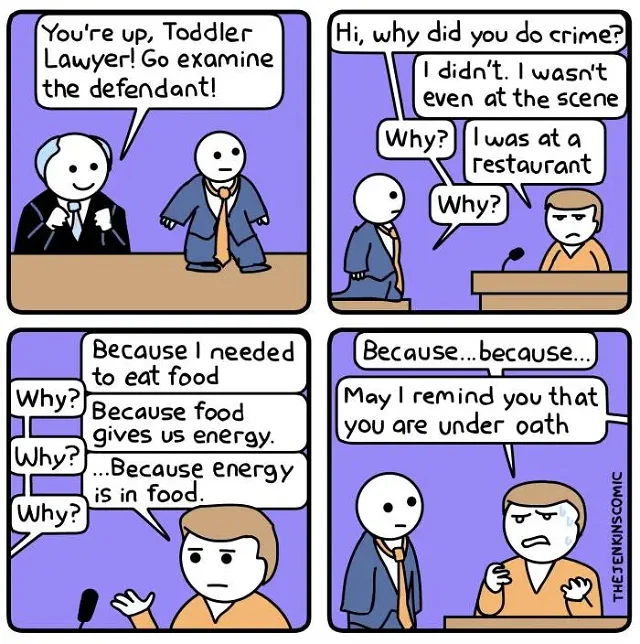

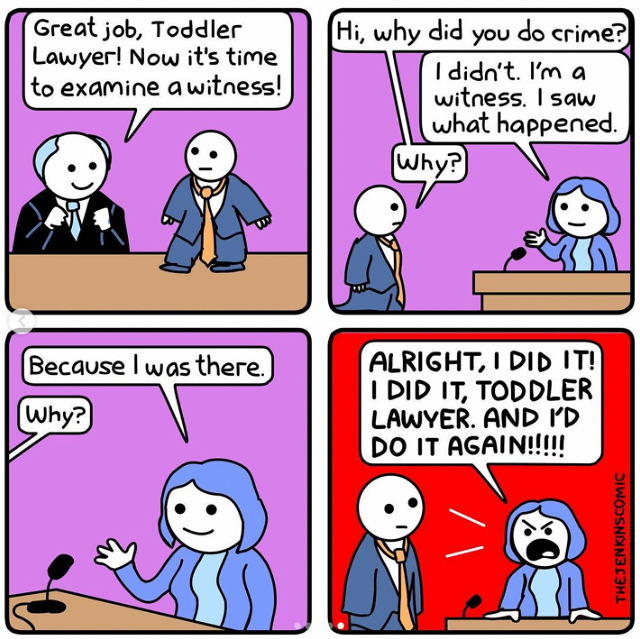

IF TODDLERS WERE LAWYERS . . .

part 2 is even better....

-"BB"-

part 2 is even better....

-"BB"-

Yes, I suppose I could agree with you ... but then we'd both be wrong, wouldn't we?

Re: Legal question

Andy--you're right to a point, but being a scientist and a lawyer, I can see both sides; as a scientist, you deal with thedata, the lawyer deals with the outcomes. the scientist reports that the data shows the killing of fish at the 10 ppb level and leave it at that; the lawyers look at what the threshold level is, how it has to be generated,what statistical significance is needed, even the size of the sample tested, etc. They look to the wording of the law to be sure they are doing what is required and consider what other alternatives there are, and then they isue their opinion. I can tell you I have shut down a lot of projects and cancelled some lucrative sales contracts because of legal problems, but only after the broader analysis I described. It might seem like muddling the truth, but it's quite different--things are rarely as black and white as you indicate.

And FWIW, most business would far prefer the black and white answer, even if it is negative, to the long and drawn out discussions--I can't tell you the number of times a senior executive said "just tell me yes or no", but I wasn't doing my job then. It's kind of like what they are now discussing about classification of documents--there is judgment calls that come into play, and it's much easier to just say "classify it"--but that's not doing your job properly (nymore than making everything public would be).

And FWIW, most business would far prefer the black and white answer, even if it is negative, to the long and drawn out discussions--I can't tell you the number of times a senior executive said "just tell me yes or no", but I wasn't doing my job then. It's kind of like what they are now discussing about classification of documents--there is judgment calls that come into play, and it's much easier to just say "classify it"--but that's not doing your job properly (nymore than making everything public would be).